GOUGE SHARPENING AND MODIFICATION

In these pages I present a discussion on sharpening and modification of

gouges,

also known as linoleum cutters or cutters for block

printing. The most commonly used tools of this sort are the

Staedtler 1V (shown above) and the Speedball #1, although these

guidelines also work with other V-shaped carving tools such as

the Staedtler 2V and V-shaped woodcutting tools. I'll go into

excruciating detail to

make the process as clear as possible, and apologize for how lengthy it

is.

Below, I describe how to sharpen one of these gouges as well as a minor

modification.

On separate pages I describe how to perform three popular major

modifications,

pinching, miniaturization

and reversing.

WHAT YOU'LL NEED: Being

able to clearly see what you're doing to the tip of your gouge is

imperative, so you're going to need all the magnification and lighting

you can muster. If you have good eyesight, drop into your

neighborhood Dollar store and pick up a pair of +3.50 or stronger

reading glasses

for a dollar. If you need glasses to see normally you won't be

able to put cheap reading glasses on top of them, so you'll need to

resort to a magnifier on a stand or something else.

Besides good magnification to see what you're doing, it's also helpful

to have great magnification

to inspect your finished work. If you have a jeweler's loupe or

similar 10X magnifier, that'd be good.

You will need a very fine knife hone; a common "knife sharpening stone"

won't do, they are usually far too coarse for this job even if they

have a side described as "fine". There are

several ways to obtain a suitable hone. You can get what's

called an "Arkansas stone", which is sold in fine knife stores; an

Arkansas stone is typically used after a regular stone when sharpening

knives because it is very fine-grained and applies a very smooth

finish to the cutting edge. An Arkansas stone may be difficult to

find, though. If you get one, be sure to get some honing oil to

use with it. They sometimes are sold together -- along with a

coarse stone -- as a "knife sharpening kit".

Another route would be to purchase a diamond hone for sharpening

knives, but

you need to make sure to get a very fine one, 600 grit or

thereabouts. Harbor Freight Tools sells a couple of models,

including some with three or four grits on the same block. The

problem with these things is that they typically have rows of holes all

over the surface, which may help sharpening knives somehow

but it just causes grief honing gouges. Still, often such

diamond hones will have a flat area uninterrupted by holes at each end

that's large enough for our purposes.

Contrary to the Arkansas stone, a diamond hone works best dry. A

diamond hone also seems to get finer with use, apparently as the high

points of the grit get broken off the surface, but it keeps on

working. It actually works a little better for this task after

it's been worn a little bit.

Yet another way to go would be to use a piece of 600-grit sandpaper

taped

down onto a flat surface such as a piece of glass. This may sound

like the quick and easy route, but it's more difficult to obtain a good

edge with sandpaper. If at all possible, the above two methods

are preferred. If you choose to use sandpaper, be sure to pull

your gouge across the sandpaper rather than push it; pushing can cause

the sandpaper to curl up a bit just ahead of the gouge and dull it

rather than sharpen it.

There are other ideas that might work. A ceramic or stone coaster

might work -- that's right, the disc your drink is sitting on while you

read this. It must have a flat surface and a fine grain --

ceramic will usually be smooth enough, but many of the stone coasters

are too coarse. The surface obviously can't be

coated with paint or glazing. If it's painted or engraved on top,

you might

try flipping it over and peeling that cork layer off the bottom.

Using the bottom is also less likely to incur the wrath of your

significant other for ruining one of your coasters.

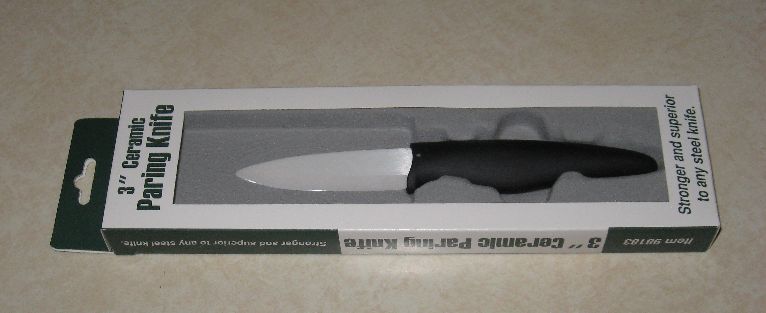

Besides the hone, you will also need a ceramic knife. It's

possible you've never heard of such a thing; they are a fairly

recent technology. Basically it's a knife with a blade made of

bright white ceramic rather than steel. The reason: ceramic

is much harder than steel, so it will hold an edge better -- and for

this task, it means it can be used to hone the inside edge of your

hardened

steel gouge without the knife itself getting polished instead.

The good

news is that you can buy a ceramic knife at Harbor Freight Tools.

They carry three sizes, a 3" paring knife, a 5" utility knife, and a 6"

chef's knife. Any size will work here, but once you have this

knife you'll want to put it to use in the kitchen, too -- trust me,

these are great knives -- so

choose the

size that would best fit your kitchen needs.

You can also buy a ceramic knife at Walmart. Side note: A

ceramic knife will cut most anything, and that includes your fine

china! Don't use one as a steak knife -- you'll notice that

Harbor Freight Tools doesn't offer a steak knife version -- because

diners would be cutting your plates as well as the steak. Use a

ceramic knife only on a cutting board or similar surface.

If you can't find a ceramic knife the only possible substitute known is

a

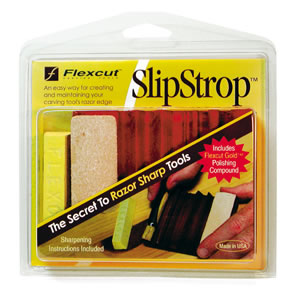

Flexcut Slipstrop, which is a honing kit designed specifically

for sharpening carving tools.

I haven't used one, but I

understand

they are made of wood and use a fine rouge or polishing compound to

provide a cutting

action. What's important here is that it have a razor-sharp edge;

a sharp edge is essential to make your gouge better rather than worse

when

sharpening. If the wood in the Slipstrop has a sharp edge that'll

be good, but if that edge gets dull with use you're either

going to have to figure out how to sharpen it or keep buying new

Slipstrops every now and then. It's probably cheaper and easier

to buy the

ceramic knife, since it'll last essentially forever -- and if it does

get dull, you can sharpen it with a diamond hone (but not an Arkansas

stone; rub your ceramic knife against an Arkansas stone and the stone

loses!).

There is one other thing you might want to make

use of, and that's a

grinder of some sort or another. Something powered by

electricity. Basically, anything with a flat grinding surface

will do, and that includes a drill or Dremel with a flat disk chucked

up in it. Honestly, if you're only working on one or two

gouges, a power tool is scarcely worth the trouble; it's more

important when Webfoot ships you a box of 120 gouges she wants

modified! For just a couple of gouges, you can accomplish the

same tasks by hand using the various honing tools described

above.

Using one of the coarser grits on a diamond knife hone works especially

well. So, in the instructions that follow, when it says to use

your grinder, remember that you can just do the job by hand if you

prefer. If you are

using a powered grinder, please note that the tip of a gouge is pretty

tiny and will overheat quickly if you're not careful. Always have

a cup of water handy and dunk it regularly during grinding to keep it

cool.

INSPECTING YOUR GOUGE: If

we could presume that your gouge was properly shaped at the factory, we

could proceed directly to sharpening. Experience has shown,

though, that a large percentage of both Speedball and Staedtler gouges

were not properly shaped at

the factory. So, using strong magnification -- a loupe or other

10X magnifier if you have it -- and good light, look

at the tip of your gouge. There are two common faults to look

for: First, are the two sides of the cutting edge the same

length? If

one protrudes forward farther than the other, we'll have to fix that

before we proceed.

The other common problem is the profile of the

cutting face when viewed from the side; the actual cutting edge should

form a straight line. If it seems to round the corner at the

bottom of the V, we'll need to fix that, too.

Note that the bottom of the tip, below the actual cutting edge, is

typically rounded. This is not a problem. It's when the

cutting edge itself curls back toward the handle that's the

problem. In other words, the grinding done to round the area

below the cutting edge went too far.

What follows is a

procedure for cleaning up that tip so it's straight before

sharpening. If you happen to be one of the lucky souls with a

gouge that was shaped right to begin with, you can skip down to

"SHARPENING" below.

CREATING A PROPER TIP:

The following process will fix

whatever's wrong with your gouge short of having been run through a

garbage disposal. Step 1: Holding the handle (not the tip!)

perpendicular to the grinding surface, grind the front of the nib a

little bit.

Looks like you're ruining your gouge, doesn't it? Aaaaack!

After you've ground just a bit, take a look at it end-on with a light

positioned to reflect off the tip. The

grinding

you have done will have created a shiny area -- or perhaps two shiny

areas. If you had the rounded bottom problem, you'll probably get

shiny spots at the top of the V, but they don't connect at the

bottom. If you had one side longer than the other, you probably

got a shiny spot on that side only. You need to continue this

grinding until the shiny area forms a complete V. Don't go

overboard and try to make it a pretty or uniform V, only go far enough

that there

are no gaps in the V. It will probably look something like this:

Now, for Step 2 you will grind

the outside along one side of that V parallel to the inside surface of the tip:

You need to know more than this illustration shows, though; you need to

know how steep to make that cut. The best way I can describe it

is: With the side of the tip against the grinding surface, the

butt end of the handle should be about 2" to 2-1/2" above the grinding

surface.

This is presuming a Staedtler handle, which is about 6" long overall.

Don't try to grind the side of the gouge all the way to a sharp edge

just yet. For one thing, if you're using a powered grinder,

you'll most certainly burn the metal; the thinner the edge gets, the

easier it is to overheat it. For now, just put a nice bevel on

the outside surface of the gouge while leaving a narrow band of the

original shiny surface remaining.

Now, obviously, flip it over and do the other side the same way:

When you're done with these flats, the gouge viewed from the side

should have a flat that looks like this:

Note that if the ground surface isn't shaped pretty much like that, you

probably did something wrong.

Next, hold the gouge right side up with the bottom of the nib against

the grinding surface, with the end of the gouge almost flat against the

surface -- just slightly nose-down, so the tip contacts first.

While holding this position, grind just enough to create a flat on the

bottom that is shaped like an elongated diamond. Do not, repeat DO NOT grind enough that you break

through to the inside of the V at the tip! You do want to grind

until the elongated diamond you are creating extends right up to

the front of the nib, though, where the two sides you ground meet at

the bottom of the V.

Note: Both Staedtler and Speedball nibs come with the bottom

ground to a rounded shape. In cutting this flat, I am

recommending a departure from the original configuration. I have

tried both ways, with a flat bottom and with a rounded bottom, and in

my opinion the flat bottom works as well or even slightly better; the

gouge has less tendency to fall into the groove you just cut.

It's also much easier to grind a flat than a curved surface. You

may, however, opt to roll the gouge side-to-side during this step to

round the bottom the way the manufacturer did it.

After you've finished this step, you're done with the grinder for

now.

SHARPENING: Hold the

gouge with the tip against the surface of the hone and rolled onto one

side, so that one side of the V is flat against the hone. The tip

of the handle should be perhaps 2-1/2" to 3" above the honing surface,

which you'll note is a bit higher than it was held in the grinding

steps described above. This will have you honing just at the

cutting edge rather that trying to move the entire bevelled surface.

The trick here is to have good light and good magnification to see what

you're doing, and hold the gouge in one hand and the hone in the

other. Firmly establish the position that you will be holding

both. Bring them together and begin a honing motion (back and

forth, circles, doesn't matter much) without changing those

positions. Periodically stop and look at the polished area you

have created, making sure that it is uniform along the edge and not

concentrating too much at one corner or the

other. If you find you've been leaning a bit crooked one way or

the other, adjust and continue.

If you have ground a new tip on the gouge as described above and left a

narrow strip of the flat front face during grinding, now is the time to

bring that

bevelled surface all the way to meet the inside surface of the V.

Note that as you get close to the inside surface of the V you need to

be applying only very light pressure on the hone. Too much

pressure will push the thin edge right over. Even if it doesn't

permanently deform it, it can bend it enough that the hone isn't

creating the edge you're looking for; it's not polishing the edge

itself because the edge has moved out of the way. Very light

pressure is the secret to success here; let the hone and the motion do

the work, don't try to rush it or force it.

Note: If you have experience sharpening knives, you're probably

alarmed at how steep these angles are. If you honed a knife at

similar angles, it would end up with a pretty blunt edge indeed and

wouldn't cut well at all.

If you try to use the shallow angles commonly used in knife sharpening

on a gouge, you'd end up with a very sharp gouge -- and you'd

bend the edge over as soon as you tried to carve with it. The

cutting

edge on a gouge nib needs to have comparatively blunt angles to

be strong enough to push into rubber and pry pieces out without getting

damaged. The fact that the tip doesn't have that razor sharpness

you get from honing at shallow angles isn't a problem because it's not

difficult to push a gouge through rubber anyway.

Obviously, once done with one side of the V, roll the gouge the other

way and do the other side.

Once you have both sides honed to form an actual cutting edge at the

face of the V, you will know perfectly well how to hold the gouge with

one side or the other against the hone while rubbing. Now do one

more trick: While holding one side of the gouge against the hone

and rubbing, slowly roll the gouge over to the other side, continuing

the honing motion all the way. Keep the handle at about the same

height through this process. When honing a Staedtler, the entire

roll should take no more

than a few seconds; it takes a bit longer on a Speedball because the

bottom of the V isn't as crisply formed. When done, you can look

at the bottom of the

V and see what you've done. This step will round the corners

where the flats on the sides and the elongated diamond flat on the

bottom meet. This is a minor and quick step, but it makes all the

difference in how well your gouge will carve because it's this area

that slides across the rubber when carving.

The next step is to take your ceramic knife and position the edge of

the knife down in the bottom of the V. The tip of the knife

should be pointing toward the handle of the gouge. With the

ceramic knife held in this position, roll it until one side of the

knife is sitting flat against one side of the V of the gouge.

Slide

the knife in and out of the tip of the gouge a couple of times; the

blade will probably come close to contacting the handle of the

gouge. You may notice a gray smudge appearing on the white

ceramic knife; that's metal particles being rubbed away. Roll the

knife over the other way and polish the other

side of the V the same way. And, just for good measure, stand the

ceramic knife up straight, centered between the two sides of the V, and

make a few more in-and-out sliding motions with the sharp edge of the

knife working on the bottom of the V only.

This treatment with the ceramic knife only takes ten seconds or

so. Two or three slides each way is plenty. It absolutely

must be the last thing done

to the cutting edge of the gouge, though. If you decide the work

on the outside isn't

quite right and you want to go back and hit it some more, be sure to

repeat the inside honing with the ceramic knife when you're done.

A MINOR GOUGE MODIFICATION:

Your

gouge

is

done,

but I recommend one more step. Hold your

gouge with one side of the tip against a grinder or hone (either works

here) as shown:

You'll need to use the corner of a grinder or hone for this task,

because you need to get down low enough that both the broad part of the

nib and the handle would be contacting the grinding surface.

Grind away the side of the tip as shown. When viewed from the

side, the resulting flat will be a triangle with a long straight side

along the top edge of the gouge tip and the peak pointing

downward. The forward end of this triangle should not meet the cutting edge!

Get it up close to the cutting edge and quit. Obviously, repeat

for the other side.

These cuts do not affect the cutting edge at all; the cutting edge is

not involved -- that's why it doesn't matter if you use the hone or

grinder. What this modification does is make the tip visibly

narrower, which means it's easier to see what you're carving because

there's less gouge in your line of sight. You'll be surprised at

how much it helps. And it's quick and easy to do.

The completed gouge should have 5 "facets" around the outside.

Two triangles, two trapezoids, and one elongated diamond.

You're done. Using a scrap piece of carving rubber, take a couple

of trial cuts and see how it works. I usually start by jamming

the tip deep into the rubber to clean it; pull it out of the rubber

and it leaves smudges of metal particles all around the cut. If

you have a jeweler's loupe or similar 10X magnifier, you can inspect

your work. The important thing is that you haven't left any of

the original shiny flat face, which would be dull. It's pretty

easy to

tell if you have, though, by holding the gouge in such a way that your

light would shine on it. When there's no more shine, you know

you're looking at a sharp edge.